I still remember my first breath of Antarctic air—that sharp, dry, crystalline burn in my nose and down my throat when we landed on the Sea Ice Runway at McMurdo Station. All those years ago, I’d explain it as some kind of utopia: no one hungry, no one unemployed, no one unhoused. No poverty, zero tolerance for violence, free healthcare, no unmet needs. It’s strange to think now that what we pulled from the ice cores in Antarctica was how very old the planet is, in relation to the dystopian quickness with which humans could end all life on Earth.

Once my kids knew how to tell time, I told them that if the whole history of Earth were squished into a 24-hour day, modern people wouldn’t even show up until about the last two seconds on the clock. Brushing my teeth in their bath steam, my index finger squeaked on the mirror a clock with the short and long hands so close together that I drew them with my fingernail. Above it I scrawled 23:59:56—next to that I drew a stick-figure human.

Afterward, we chewed pink, dissolvable tablets to see where the bristles left debris on our teeth. The boys pretended that they’re brain-eating zombies with bright ooze dripping from their lips. I thought of how few bees were in the garden orchard, that perhaps one day my kids’ diet may consist of roots, raw fish if they’re lucky, small insects with exoskeletons that crunched like chitlins.

Brains, they said climbing on the toilet seat to reach my head. If you had any, I snapped, you’d take brushing your teeth seriously. They stopped and looked at each other, looked side-eyed at me. I spat out my toothpaste with extra vehemence, suddenly angry at their apparent flippancy, as though it revealed a certain privilege I hadn’t had when I lost my baby teeth in a refugee camp where my mom brushed my teeth with a rag wrapped around her finger when I was their age.

It was a fine line between breaking generational trauma and enabling entitlement—one I skated with obvious unease mostly, but not always, in my mind. That night, I opened the medicine cabinet, took out their favorite strawberry-flavored toothpaste and threw it in the trashcan.

Yesterday and a lifetime ago, E pulled a crooked carrot straight from the ground and lost a baby tooth biting into it. He cried because it had fallen somewhere in all the vermiculite and now there would be nothing for under the pillow. No money to dash off to the donut shop for a half dozen glazed holes.

In my desk drawer, a tidy little matchbox from Oslo with decorative, alpine flowers on one side, a geometric pattern of stars on the other. A strange collection of tiny teeth that rattled inside, although I’m too squeamish to ever really look closely at them. I only ever lift their sleeping head, take the tooth out from underneath, leave a two dollar bill, and pour the new, lost star from my fingers into the matchbox. Then I slide it shut again, quietly, without a peep.

In Susan Sontag’s 10 rules for raising a child, number nine is this: “Make him aware that there is a grown-up world that’s none of his business.” But my third-grader can explain viruses and how they mutate. He starts by telling us to imagine someone in spiky armor battling an inconsequential clone army. He ends by asking since they’ve already brushed their teeth, can they please watch a little tv?

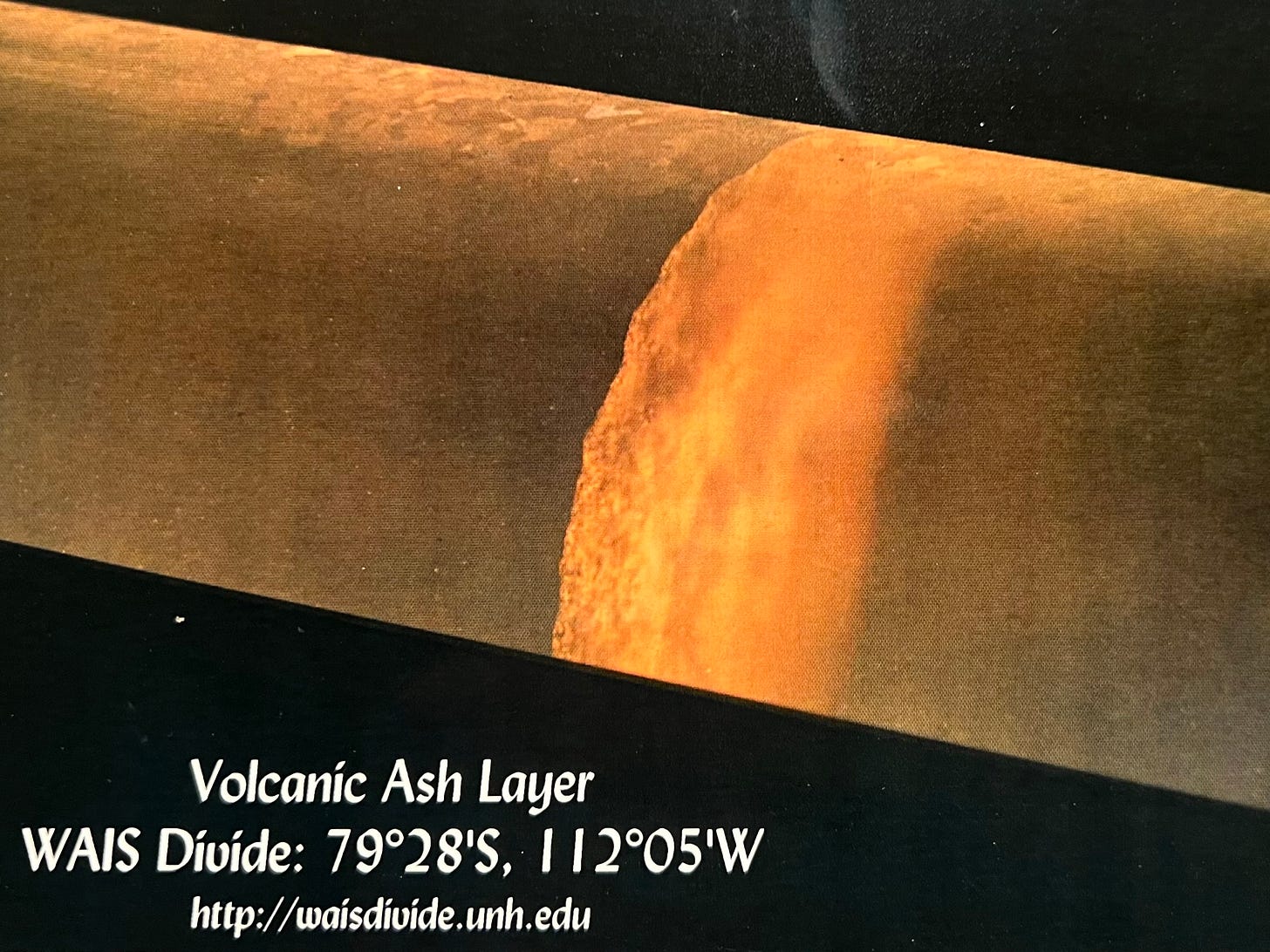

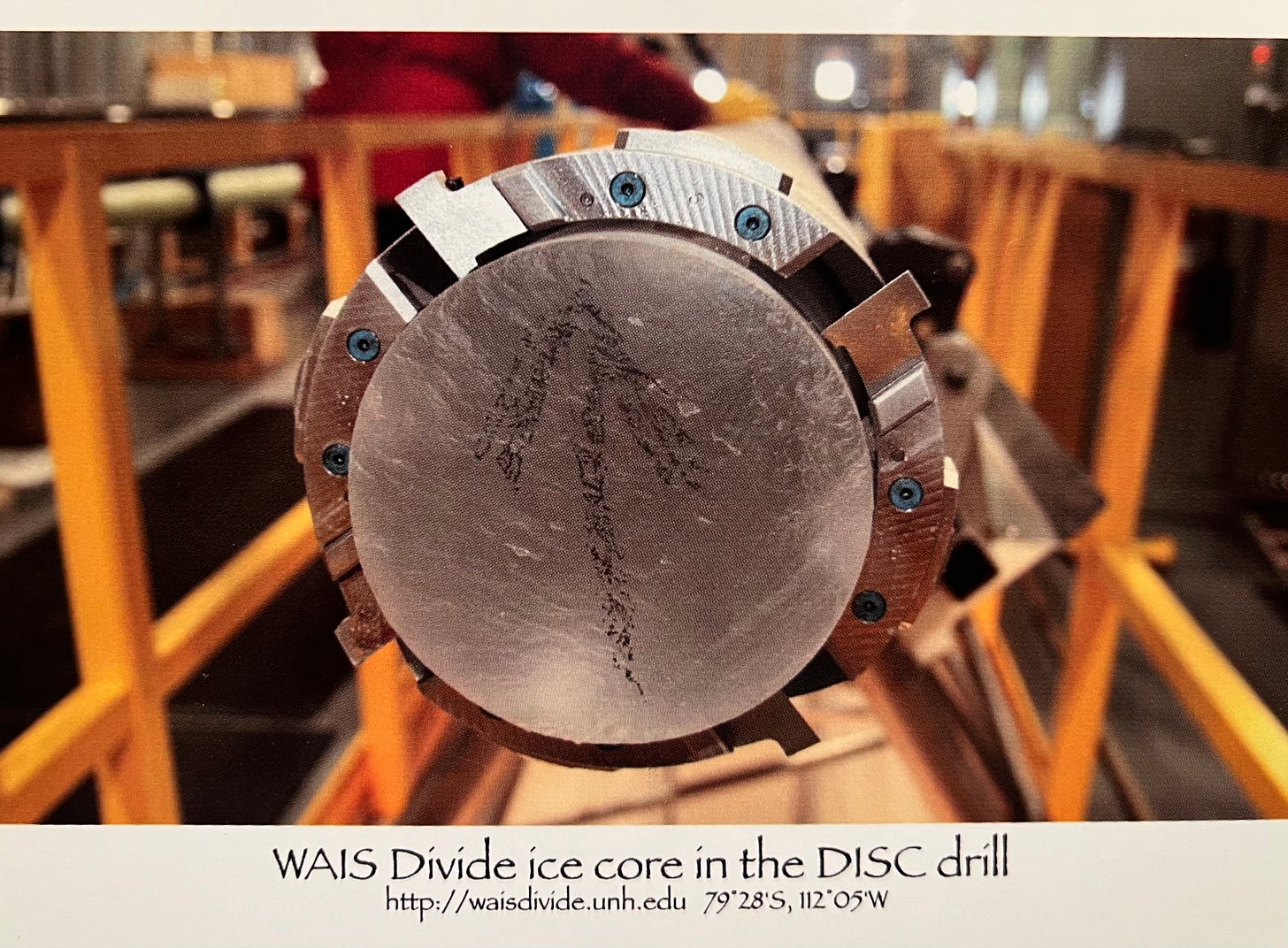

What time is it? They ask yawning. It’s eight thirty at night, and Earth is very, very cold. Think of a giant snow cone, lumps of ice compacted and round. Below 50 million years of ice, Earth’s fiery core. Think of a cinnamon Red Hot lodged at the center of a packed, icy snowball.

In the time it takes the boys to pull off their hoodies and t-shirts, to kick out of jeans and crumple it all into the hamper, the climate has fluctuated back and forth between the big freeze and retreating ice.

140 million years later I kiss their sweaty, salty heads—and life explodes from the sea.